Spinal pain - Assessment - (3.3.11 - 3.3.17)

- robinapark

- Apr 18, 2021

- 15 min read

Updated: Mar 7, 2022

3.3.11 - Identify and take appropriate action in potential specific causes of acute spinal pain ("Red flag conditions")

Infection

History and diagnosis:

(Yusuf, Finucane & Selfe, 2019; UpToDate Vertebral osteomyelitis and discitis in adults 2021)

Clinical consensus for evidence for red flag conditions is poor (Yusuf, Finucane & Selfe, 2019). Spinal infections do not always have a long lead time. Up to 50% of patients will only be symptomatic for up to 3 mths.

The classic triad is fever, spine pain, and neurologic deficits (Davis et al., 2004).

Back pain is the most common presenting symptom (71% of cases)

Staph aureus is the most common causative organism in spinal infection (>50% - UpToDate)

Unfortunately (or fortunately?) the incidence of spinal infection is 0.2-2.4 cases per 100,000 annually, which makes a prospective diagnostic study somewhat impossible.

Risk factors can be helpful: Diabetes, IV drug use, past history of TB, use of corticosteroids or immunosuppression (including cancer and HIV), and fever. Recent surgery is obviously also a marker for possible spinal infection.

Spinal infection is commonly a disease of people >50 years of age

Infection commonly comes from either: Haematogenous seeding, contiguous spread, or direct inoculation from trauma or procedures.

Work up:

Plain films can be used by sensitivity is pretty poor (40-70%) (Palestro, Love & Miller, 2006). MRI is better than CT - though CT can be used where MRI is not accessible. Radionuclide scans can be used and are quite sensitive, but specificity is poor.

Inflammatory markers (ESR and CRP), Cultures (blood and urine - positive in up to 50% of cases) and imaging.

MRI sensitivity is good = ~95%.

Can consider biopsy of the affected bone and aspiration of abscess. This can be used for culture and focusing therapy

Treatment:

Surgery if ongoing neurological deficits, evidence of epidural or paravertebral abscess, or cord compromise.

Antimicrobial therapy chosen guided by sensitivities and cultures. Duration of therapy is generally prolonged - >6 weeks.

Prognosis:

Complications are commonly from neurologic impairment from either abscess formation or bony collapse. Back pain may become chronic. Best outcome is early therapy. Mortality is ~5% (commonly with co-morbidities)

References:

Davis DP, Wold RM, Patel RJ, Tran AJ, Tokhi RN, Chan TC, Vilke GM. The clinical presentation and impact of diagnostic delays on emergency department patients with spinal epidural abscess. J Emerg Med. 2004;26(3):285–91.

Palestro CJ, Love C, Miller TT. Imaging of musculoskeletal infections. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2006;20(6):1197–218

Yusuf, M., Finucane, L. & Selfe, J. Red flags for the early detection of spinal infection in back pain patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord20, 606 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-019-2949-6

Fracture

History: (UpToDate - Evaluation of low back pain in adults)

Vertebral compression fractures may be identified in ~4% of patients in a primary care setting. Some have no symptoms, and some cause intractable pain.

BEWARE - there may also be no clear history of trauma. Otherwise, there may be a history of innocuous trauma such as coughing, sneezing, or going over a speed bump.

The best 3 questions to ask in a Cochrane study for vertebral fractures were:

Use of steroids

Increasing age (particularly >74yo)

History of recent trauma

Pain is usually localised to the midline spine but can refer to flank, anterior abdomen, or PSIS. Radiation to the legs is rare.

Pain may be sharp or dull. Sitting, spine extension, Valsalva, and movement often exacerbate the pain. Palpation and percussion of the spinous process involved often exacerbate pain.

Height loss may occur - > 6cm! (can be quite specific)

Osteoporosis is clearly a big risk factor - and the risk factors for this include age, and chronic glucocorticoid use. The previous fracture is a risk for future fractures.

Kyphosis can occur as a complication of multiple fractures. A wedge fracture may cause loss of 1cm. 4cm of loss leads to ~15 degrees of kyphosis.

Kyphosis often leads to no waist, clothes that don't fit, and may experience early satiety (due to compression of abdominal contents). It can be so severe that patients can experience costo-iliac impingement - where the 12th rib rubs on the iliac crest.

Examination:

Neurological examination is important as their presence may indicate retropulsion bone fragments into the spinal canal or foraminae that may require surgical intervention. Urgent MRI should be sought in these cases.

Investigation:

Generally plain films give enough information. Only CT or MRI if there are further concerns.

Management:

Oral analgesics sch as simple analgesia or weak opioids.

Most patients can be managed conservatively without vertebral augmentation. Vertebral augmentation can be considered in cases of intractable pain.

Physical activity as early as possible is crucial to prevent bone loss and deconditioning

Remember to treat underlying osteoporosis and its causes

Evidence for vertebral augmentation and cement is minimal. Those not settling with every other modality, should be referred for this to be considered.

Vertebroplasty also has mixed evidence. Kyphoplasty is possible - but sounds odd.

Braces are not recommended.

Prognosis:

The majority of these fractures will resolve in 4-6 weeks but may take longer. Severe back pain beyond this time warrants further investigation. Functional limitations are common - as is chronic pain (up to 75%).

References:

UpToDate - 2021

Williams CM, Henschke N, Maher CG, van Tulder MW, Koes BW, Macaskill P, Irwig L. Red flags to screen for vertebral fracture in patients presenting with low‐back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD008643. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008643.pub2. Accessed 18 April 2021.

Neoplasm

History:

Spinal malignancy is a very rare cause of low back pain

Back pain due to spinal malignancy may be associated by the patient with movement or trauma. It may also relate to compression fractures from bony infiltration and weakness.

Acute pain within the back without a history of trauma should be fully explored

Pain within the back is commonly due to stretching of periosteal structures with cortical expansion. Neural compression and neurological deficits may follow.

The two red flags with most significant support for diagnosing back neoplasms was:

High clinical suspicion

Previous history of malignancy

E.g. Vertebral metastases have been found at autopsy in 90 percent of patients who died of prostate cancer, 74 percent with breast cancer, and 45 percent with lung cancer

Metastatic malignancy accounts for 95% of vertebral fractures

Five other flags to consider include increasing pain at night, pain not eased in a prone position, continuous pain at rest, thoracic pain, pain not worsened during movement. Age >50 years is also reported as a common finding.

Elevated ESR would also reinforce the risk of malignancy

Physical examination:

Examining the back with a particular focus for neurological findings

Tenderness of the spinous process is uncommon in other non-trauma non-cancer-related disease

Investigation:

Plain radiographs can identify 80% of benign tumours and can pick up other malignancies. However, at least 50% loss of trabecular bone is required for malignancy to be identified on plain radiographs.

The 'winking owl sign' is evidence of loss of bony opacity in one corner of the vertebral body.

Opacified material sitting outside of the normal rectangle of vertebral body should indicate further investigation is required

Bone scintigraphy is very sensitive but not very specific. It can also highlight the primary.

CT can be used, but better is MRI. Particularly as it shows the soft tissues and neural tissues.

Prognosis:

Prognosis depends clearly on original cancer in the setting of metastasis.

Further morbidity and mortality can be related to unstable vertebral structures due to weakness and also neurological compromise

References:

Verhagen, A. P., Downie, A., Maher, C. G., & Koes, B. W. (2017). Most red flags for malignancy in low back pain guidelines lack empirical support: a systematic review. Pain, 158(10), 1860-1868.

Neurological involvement (Transverse myelitis)

History:

Transverse myelitis:

- Symptoms develop over hours or days and worsen over days to weeks

- Can present with sensory changes, weakness, autonomic changes such as bowel and bladder, hypertension and thermoregulatory problems

- It usually starts with paraesthesias in the feet and sometimes associated back pain at the same level

- Motor symptoms can then present and worsen along with the autonomic changes

- For example, Brown-Sequard lesion is where it involves one half of the spinal cord. This is interesting because it, therefore, affects dorsal column dysfunction on the IPSILATERAL side of the lesion, and spinothalamic changes on the CONTRALATERAL side to the lesion. (Often due to MS or a compressive lesion)

- Complete cord loss is more commonly from an acute compressive lesion, necrotising myelitis, syrinx, or trauma.

- Complete lesion will have both side spinothalamic, dorsal column, and autonomic changes below the level.

- Often hard to differentiate between compressive myelopathy and transverse myelitis

- It is called 'Transverse' because there is often a band-like neurological loss at the level associated with the inflammation (These days the term is more used to describe whether the inflammation is partial or completely across a spinal level).

Investigations:

MRI is best though CT myelography can be considered for structural causes but it won't show the spinal cord

If in doubt, always image slightly above the suspected pathology as this can otherwise be missed (e.g. ordering only a lumbar MRI and the lesion is in T12).

LP can be useful to look for evidence of inflammation. If absent, consider vascular, toxic, neurodegenerative and/or neoplastic lesions.

If it is inflammatory, then the possible etiologies are broad!

Treatment and prognosis

These clearly depend upon the causative agent and are beyond a brief discussion here.

Corticosteroids, antibiotics, HIV therapy, and surgery - are all possible to consider dependent upon the cause.

Plasma exchange can be considered, as can immunosuppressive therapies if required.

Reference:

West, T. W. (2013). Transverse myelitis—a review of the presentation, diagnosis, and initial management. Discovery medicine, 16(88), 167-177.

Neurological involvement (Cauda Equina)

Background

- Remember - the Spinal cord ends at L1/2 and then continue as nerve roots

- Cauda equina syndrome is damage of these nerve roots anywhere through their traverse to their target locations

- It can be compression, infection, ischaemia or venous congestion

Lower limb movement (L2-S4), bladder, bowel, and perineal sensation (S2-S4), and coccygeal innervation (S4-S5)

Loss of innervation to bowel and/or bladder leads to retention and loss of voluntary control. This can lead to overflow.

It is commonly caused by large central disc prolapse at L4/5, or L5/S1 (one of these in 45% of cases - though remember, CES only occurs in less than 1% of disc prolapses)

Delay to diagnosis is common (median 11 days!)

History:

Rapid onset without back problems

Acute bladder dysfunction with back pain and possibly sciatica

Chronic back pain with or without sciatica, with slow onset of bowel and bladder symptoms

Most common presenting:

Back pain

Bladder dysfunction

Saddle hypoaesthesiae

70% of patients had a chronic back problem prior to acute CES (note 30% did not!)

CES can present slowly over weeks to months

You can have incomplete CES with just increased difficulties with urination

Typical red flag features include: Bowel and bladder incontinence (though faecal is less commonly reported), loss of saddle sensation (though this may be patchy, and needs to be asked about specifically), severe lower back pain, bilateral sciatic symptoms (though unilateral sciatica is more common than bilateral), and sexual dysfunction (urination during intercourse, erectile difficulties, dyspareunia)

Obviously important to ask a time course and particularly any association with recent spinal interventions

Unusually for sciatic pain, the pain is usually worse when supine (as increases pressure across the spinal canal). Pain is often more severe also than with a single nerve root involved.

Lower limb weakness is also seen.

Physical examination

Lower limb strength (L2-S3), perianal region sensation (S2-S4), patellar and achilles reflexes (often reduced in CES).

Anal wink reflex can be tested with cotton wool brushed close to the anus

Rectal tone is not routinely assessed as has not been shown to be overly helpful and variability between examiners is high

Investigations

Basic blood panel and clotting factors

Bladder US for post void residual

Plain X-rays are not very helpful

MRI is the imaging of choice (81% sens and 81% spec for large disc herniation causing CES)

CT Myelography is a second choice

Treatment

Immediate surgical intervention - Ideally <48 hrs after onset of symptoms

Reference:

Long, B., Koyfman, A., & Gottlieb, M. (2020). Evaluation and management of cauda equina syndrome in the emergency department. The American journal of emergency medicine, 38(1), 143-148.

3.3.12 - Identify specific conditions associated with chronic spinal pain including but not limited to:

- Diseases of bone

Pagets disease can cause a gnawing type of pain

Simple analgesics and NSAIDs are helpful

Bisphosphonates work best - healing lesions and improving quality of life and reducing pain

- Inflammatory disease

- Neoplasia

3.3.13 - Recognise the clinical presentation of symptomatic central canal stenosis

History:

The most common presenting reason is a pain in the lower back, buttocks, thighs and legs.

Often a cramping or burning sensation

Symptoms vary from a mild aching in the sacral region through to severe sharp debilitating pain in the back, thighs, legs and feet

Can be bilateral but is rarely exactly symmetrical (but remember those with foraminal disease it is rarely bilateral)

Balance, sensory loss, and weakness can all occur

It nearly always occurs with back pain, but lower back pain without some leg involvement is rare

The cardinal symptom is neurogenic claudication

This is brought about as an increasing ache, numbness and/or weakness in the lower back and worsening pain into the buttocks, thighs and legs with a particular posture particularly standing, walking and lumbar extension

Symptoms are often improved by sitting forward or the 'shopping trolley' sign

Differentiating between vascular and neurogenic claudication is easy as rest improves vascular claudication whereas alteration of position improves neurogenic

Symptoms below the knee are also more common in vascular claudication

Pathophysiology

Not clear. Either vascular (not enough blood) or venous drainage problems (not enough clearance of metabolites)

Inflammation is NOT thought to play a significant part

Diagnosis

There are no clear diagnostic criteria

(age, radiating pain when standing and relief when sitting, improvement when leaning forward, and broad-based gait are the main history features)

Balance problems, evidence of weakness, loss of reflexes, and sensory deficits are key in examination

Investigations

Electromyographic studies can be used - but are hard to access and protocols are unclear

MRI is the most important study - but again it does not have clear criteria

Also, it is only really useful when planning surgical interventions or similar

The most useful findings are a central disc bulge and/or perineural intraformational fat

The 'sedimentation sign' shows a spinal cord that will not 'settle' with gravity on supine MRI has some suggested good sensitivity and specificity for severe LSS

Management

Non-Surgical

Insufficient evidence to recommend one therapy over any other

Pharmacological

Vitamin B1, Gabapentin, and prostaglandin E1 (some good evidence in short term follow up) have been considered. Minimal evidence at best

Calcitonin is no better than placebo

NSAIDs are unhelpful - as are opioids and muscle relaxants

Physiotherapy

Very little evidence

Maybe just improve activity and advocate weight loss seems to be the best options

Injections

Epidural evidence varies significantly. Uncertain. Some suggestions of improvement but not much benefit of steroids

Surgical:

Generally is elective as sudden deterioration is significantly rare

Which surgical approach to taking remains unclear

Surgery generally works better here than in other patients with back pain

Particularly the radicular symptoms, less so the lower back symptoms

Some evidence surgery is better than waiting and watching - over a 10 year follow up study

Generally, only 60-70% are happy with their symptoms after surgery (Which sounds quite good?!?)

Prognosis

Surprisingly this is not overly clear but it is unlikely that the disease significantly worsens with time. It is not clear that this is a 'degenerative' condition

Different studies have suggested slow progression, to improvement in 1/3rd, to no change over 8 years!

References:

Lurie, J., & Tomkins-Lane, C. (2016). Management of lumbar spinal stenosis. BMJ, 352, h6234–h6234. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h6234

3.3.14 - Critically appraise commonly used provocative clinical tests, including but not limited to:

Lasegue/SLR test

The straight leg raise is a controversial examination provocative procedure. The theory is that by straightening the leg with the knee extended, you progressively stretch the sciatic nerve. Inflammation at a site of the sciatic nerve may lead to exacerbation of pain within a particular area.

Usually, the foraminal nerve root has an available excursion of 4mm. Though, it is postulated that reduction in this amount may correlate with evoking radicular pain sensation. It is important to remember that mechanical compression alone does not cause pain.

Additional SLR tests include the Bragaad's sign (dorsiflexing the foot), Neri's sign (flex head forwards) and the crossed straight leg test (straightening the OPPOSITE leg causes pain in the AFFECTED leg)

It is reported as being highly sensitive for lumbar disc protrusion (92%) but having poor specificity (10-42%). It is likely a better test to help rule out lumbar disc protrusion.

Reference:

Willhuber, G. O. C., & Piuzzi, N. S. (2020). Straight leg raise test. StatPearls [Internet].

Slump test

The slump test is an extension of the SLR test. This can be done in a seated position.

It differs from the SLR in that it adds spinal flexion to therefore can potentially generate greater overall neural tension.

The sensitivity is slightly less than for the slump test and specificity is similar (though study data is even less in this test than for SLR).

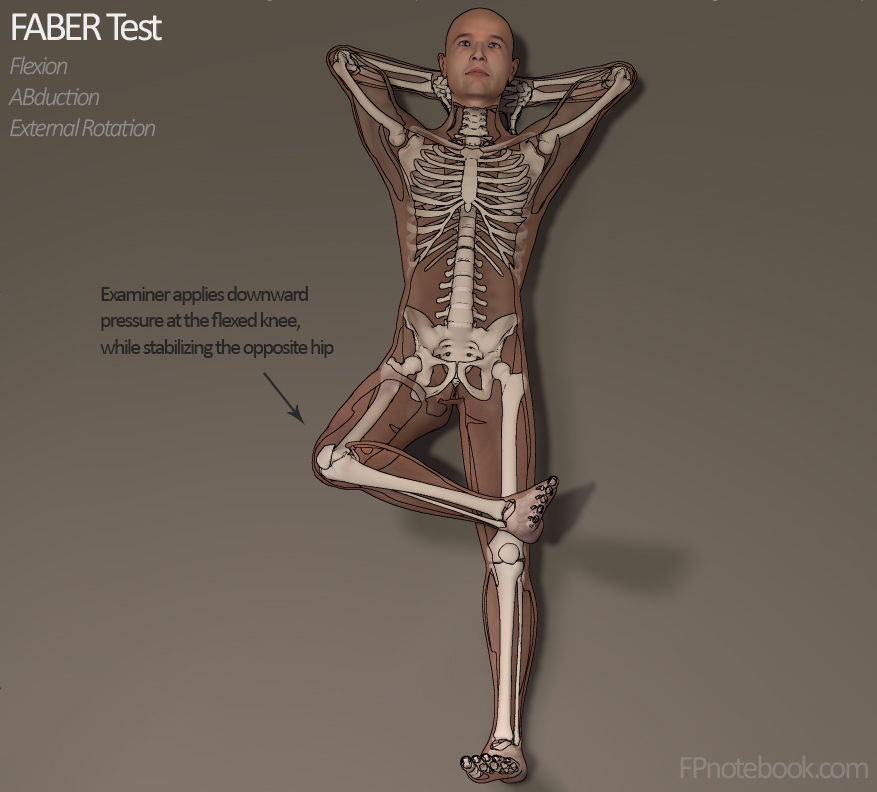

FABER Test

The FABER test applies pressure to the bilateral sacroiliac ligaments and hip joints.

Its sensitivity was 82% (but specificity is unclear and all over the place)

The validity and reliability of the FABER test are very contradictory, some say it is an invalid and unreliable test, while others disagree about the outcome and feel physical diagnostic tests do not have enough quality evidence to support their use for diagnosis purposes.

Reference:

Hilal Telli, M. D., Serkan Telli, M. D., & Murat Topal, M. D. (2018). The validity and reliability of provocation tests in the diagnosis of sacroiliac joint dysfunction. Pain Physician, 21, E367-E376.

Gaenslen test

Used to test for SIJ dysfunction

The patient starts supine with the painful leg resting on the table. Examiner sagitally flexes the non-symptomatic hip, while the knee is also flexed (up to 90 degrees).

The patient should hold the asymptomatic leg with both arms while the therapist stabilises the pelvis, and applies passive pressure to the symptomatic leg to hold it in a hyperextended position. The downward force is applied to the lower leg (symptomatic one) putting it into hyperextension while a flexion force is applied to the flexed leg. This causes torque upon the pelvis.

If normal pain is reproduced, this is said to be positive for a sacroiliac joint dysfunction, hip pathology, pubic symphysis problem or an L4 nerve root lesion. Femoral nerve may also be stretched with this test.

Sensitivity - 45-70%, Specificity 75%

Quadrant test (two - one for hip and one for back)

This is a test to assess hip pain as a pain generator. Also known as the quadrant scour test

Kemp's test (other name)

Patient stands upright and then extends, rotates, and the examiner applies pressure to the lateral spine. This is suggested to indicate a lumbar posterior facet syndrome. Local pain indicates a facet cause whereas radiating pain into the leg is more suggestive of nerve root irritation (especially if felt below the knee).

Thought to have sensitivity of 50 - 70% and specificity of 68%

Femoral nerve stretch

This is used to screen for sensitivity to stretch of soft tissue at the dorsal aspect of the lg, possibly related to nerve root impingements. It can be used alongside the SLR - and is somewhat more useful for upper lumbar nerve segment testing.

A prone knee bending test stretches the neural tissues from the femoral and mid-lumbar nerve roots (L2-L4).

Patient lies prone, therapist stands on affected side and stabilises the pelvis to prevent anterior rotation with one hand. With the other hand, the therapist maximally flexes the knee to end range. If no positive signs are elicited, the therapist can proceed to extend the hip while maintaining knee flexion.

Normal response - Knee flexion allows heel to touch the buttocks and a pull or stretch is felt in the quads.

Positive test - Unilateral pain in the lumbar region, buttocks, posterior thigh, between 80-100 degrees of flexion in is considered positive. Dura is tensioned at these angles and could be indicative of a disc herniation affecting L2, L3 or L4. NB: If pain is felt BEFORE 80 degrees

then it is more likely this is quadricep tightness and/or injury. Important to compare sides.

Sensitivity and specificity for this test is unknown.

3.3.15 - Perform and interpret a gait analysis relevant to spinal pain

Finding exact details for this question was difficult

Most studied are changes in lumbar spinal stenosis

As symptoms are worsened when standing upright and walking patients often ambulate with a forward stoop and slightly flexed hips and knees to reduce pain and increase walking tolerance

The 'Hopalong cassidy' sign can be seen for hip pain. He was called hopalong cassidy because he was shot in the leg. The patient will automatically shorten the stance phase to minimise amount of time that the painful hip is bearing the weight of the upper body.

The waddling gait sign - for osteitis pubis. Ask the patient to walk towards you quickly. They won't be able to do so easily and instead will 'waddle' to try and reduce pressure on the pubic symphisis.

Reference:

Perring, J., Mobbs, R., & Betteridge, C. (2020). Analysis of Patterns of Gait Deterioration in Patients with Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. World Neurosurgery, 141, e55–e59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.04.146

Waldman, S. (2021). Physical diagnosis of pain : an atlas of signs and symptoms (Fourth edition.). Elsevier.

3.3.16 - Discuss the limitations of medical imaging in understanding spinal pain

Acute pain:

There is no evidence that obtaining X-rays in patients presenting with mechanical lower back pain leads to better patient outcomes

Xrays MAY be useful in the setting of red flags suggesting further investigation

MRI and CT may be used in patients with severe or progressive neurologic deficits with serious underlying conditions such as vertebral infection, CES, or cancer with spinal cord compression.

A suspected herniated disc is NOT an indication for imaging as most of these also resolve with conservative therapy. MRI or CT could be considered at 6 weeks if ongoing neurology and discomfort. Routine advanced imaging is NOT associated with improved patient outcomes

Commonly, MRI and CT findings are POORLY correlated with symptoms. For example, 22-40% of asymptomatic adults who undergo an MRI will show a bulging disc

Bone scans have a limited role in acute pain. They can differentiate between an acute vs healed compression fracture as new fractures will appear 'hot'. It has a very limited role in acute lower back pain.

References:

Lateef, H., & Patel, D. (2009). What is the role of imaging in acute low back pain?. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine, 2(2), 69–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-008-9037-0

Chronic pain

MRI displays a large prevalence of abnormal findings among individuals without LBP.

These irrelevant findings can lead to significant emotional stress, utilisation of down-stream resources and even unnecessary interventions such as surgery.

Important to remember that a BULGING disc is not a HERNIATED disc.

defined as the presence of disk tissue diffusely (> 50% of the circumference) extending beyond the edges of the ring apophyses

Studies have not been able to show any MRI abnormality associated with pain for most patients with LBP.

American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society recommend only performing imaging for patients who have severe or progressive neurologic deficits or signs or symptoms suggesting a serious underlying condition. Imaging just increases, costs, exposes patients to harms, and does not improve clinical outcomes.

Chronic lumbar back pain rarely has one clear pain generator. And once peripheral and central sensitisation sets in, even reversing the original cause is unlikely to solve the pain

3.3.17 - Demonstrate ability to interpret results of electrodiagnostic (traditionally but less accurately called 'electromyography') tests

Use:

Electrodiagnostic testing helps to precisely localise disease processes affecting the nervous system (peripheral nerves, neuromuscular junctions, and muscles). It can demonstrate muscle diseases, neuromuscular junction problems, axon loss, or deymyelinating disease.

Background:

It is two different but related procedures:

1. Nerve conduction studies

2. Needle electrode examination

Nerve conduction studies

Involves stimulating motor, sensory, or mixed nerves through the skin with electrical current

Recording electrodes placed on skin over nerves and muscles capture the electrical response

Sensory studies record response in nerve fibers

Motor nerve conduction studies record response of a muscle

Values include: Amplitude and morphology of responses, velocity, and latency

"Late" responses including the F wave and H reflex measure integrity of proximal portions of nerve and corresponding nerve roots.

Demyelinating diseases (e.g. compression issues)

Axon loss -

Comments